1 – "Poetry incarnate"

Language, story and voice are uniquely important to Hungarian culture, in large part because the language itself is so unique. Hungarian, or Magyar, belongs to the Finno- Ugric family of languages, which includes Finnish and Estonian. But it is distinctive in sound and structure from other languages in this family, and unrelated to the Indo- European languages that surround the Magyar homelands. It is an “agglutinative” language, using suffixes and prefixes to imply meaning. This to me is one clue as to why magyar is so rhythmic, melodic, and ultimately poetic. George Bernard Shaw wrote that in Hungarian “it is possible to precisely describe the tiniest differences and the most secretive tremors of emotions.”

The poets and the storytellers hold a hugely important place in life here that feels profound on an emotional as well as a social level. The history of Hungary is a history of turbulent invasions and separations, and externally drawn borders. The poets of Eastern Europe often needed to write in surrealistic verse, in hidden message, in times of persecution of ethnic language and culture. Many poets here were also important political figures.

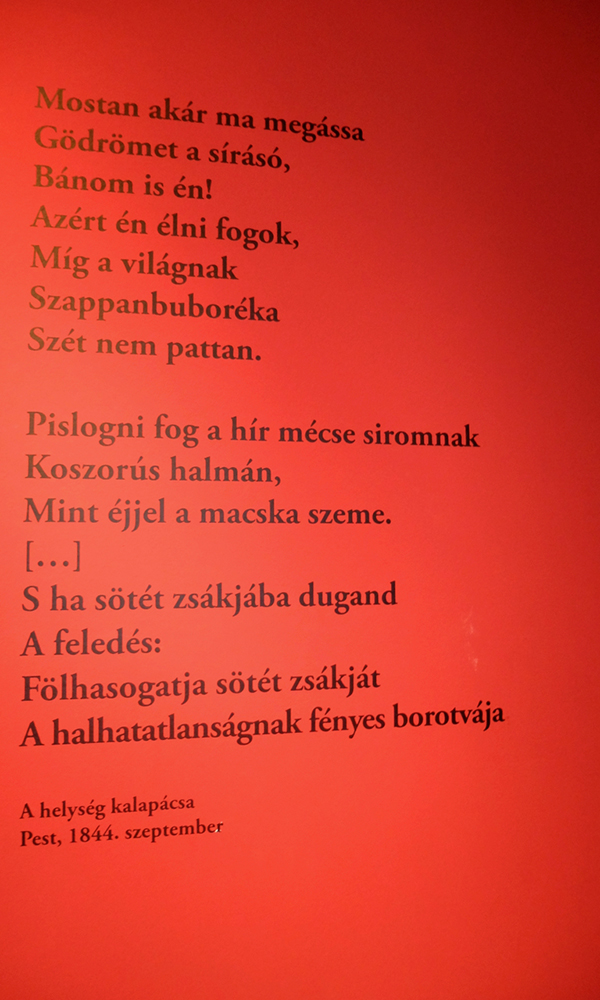

During my first week in Budapest I visit the Petöfi Museum of Literature. The introduction to the exhibition seems to encapsulate the sensibility of where I find myself: “Sándor Petöfi is much more to Hungary than an important poet, rather he is seen as poetry incarnate.”

Petöfi was a liberal revolutionary, the author of the Nemzeti dal and the 12 points list of demands. He read the latter aloud in Pest in March 1848, drawing together a crowd who began chanting the refrains, marching through the city, declaring revolution... Ultimately, he fought in the Hungarian revolutionary army and apparently died in action, although legends differ.

The mythology surrounding Petöfi is powerful, and it has been a powerful introduction to this place. But it is not only this important poet who defines Budapest. The city is peopled with statues to the great poets, and street names and bridges are named after them. It is a city of stories.

So, I’m in the right place...

I know that I could not hope to learn enough of Hungarian to even break the surface, and since this residency is happening three months before I intended, I arrive with a hopelessly tied tongue. What saves me in this situation, I think (I hope) is that I have arrived to listen. I have not arrived as an expert, translator, or even interpreter. I am not here to refract Hungarian poetry or language for other audiences. I am hear to listen, learn, absorb, and create a musical composition through the instruments that Hungary offers to me, to explore the very act and practice of listening. The sounds, voices, harmonies, notes, rhythms, refrains of the cities, countryside, and stories.

I need a guide through this journey, more than a translator – a navigator. On arrival in late June, I discover the work of Hungarian storyteller Zalka Csenge, and send an email. I state my wish for the work to be created in collaboration with Hungary, not as an outside interpretation of Hungary’s storytelling tradition and sounds, but as an open, imaginative response to the stories of this place, as well as an exploration of “deep listening” - of creating ideal sound environments for receiving stories.

Csenge and I meet in a coffee bar and she tells me, not long after we’ve begun to talk, the story of the Twelve Dancing Princesses. “The shoes that were danced to pieces.”

Image courtesy Zalka Csenge’s blog: “The shoes that were danced to pieces” by Elenore Abbott 1920

She tells me of the different dialects, and regions, of Hungary and surrounding cultures, across current borders. Slovakia, Croatia, Transylvania ... Magyar.

The variations in this story in particular, that reveal influences of cultural change and social law, in particular the control and subordination of women. Shamanistic tales overlaid with Christian morals. It is one of Csenge’s favourite folktales, and she has written about it on her blog (which is a rich and interesting read):

“Some fairy tale researchers note that "shoes" can be symbolic for sex and sexuality. Add that to the pregnant princesses and the father's (and the male protagonist's) violent judgment, and it is clear what these stories were told about: Girls overstepping their boundaries and "dancing" with men in secret, out of wedlock.

There is also a mythical/religious element to all this - secret trips into the Other World slowly turning from alluring fairy dances to witches' Sabbaths or journeys to Hell, and girls being punished for the mentorship of older, "sinister" female figures in the art of breaking free of the palace at night.”

We discuss the broad seven regions of Hungary. Whether we could gather together seven different versions of this one folktale from each of these regions, seven storytellers speaking in seven dialects, in concert and harmony with one another, ‘dancing’ in the spatial dimensions of the 4DSOUND installation. Seven women storytellers, both young and old – only women. Csenge makes an interesting point in her blog that most of the versions she has found of this story were by men.

If this is a moralistic tale of transgressive women (and their punishment and ultimate capture/release) how interesting is it to interpret this, in many manifestations, in the embodied/disembodied female voice…

I’m excited - and daunted - by this idea. To find and record seven storytellers is one thing. Csenge is enthusiastic and incredibly knowledgeable and connected with the global folklore and storytelling community. I invite her to be my co-creator on this project, and in many ways I feel that she is the soul of the story of this installation. The language and the culture.

Realising this idea technically is daunting to say the least. To weave seven voices together, in a way that is not only interesting sonically but is also entertaining and - critically - gives justice to the telling of the story … this is not going to be easy.

But this is also an opportunity to really explore the power of spatial sound as a way of challenging audiences to really listen, and to really listen in different ways.

I believe 4DSOUND may possibly be one of the only spaces, systems, where it really will be a cohesive experience to listen to multiple storytelling voices simultaneously; to absorb the sensibility of different landscapes and environments and rhythms and melodies of language, spatially. I’m only just learning the system at this point but I feel this to be possible.

Can the spatial sound environment in itself allow for more complex listening experiences? Normally an idea like this would have a great many restrictions, boundaries, in order to maintain cohesiveness, “listenability”. Is this studio going to enable me to weave these voices together in more harmonious ways?